Every Gründerzeit building enthusiast will be familiar with them: monochrome or multi-coloured tile floors adorned with ornaments or geometric patterns, smooth or with a pressed-on mosaic structure. They usually grace well-frequented areas, such as house entrances, hallways, staircases, verandas, balconies, foyers or shops. Anything from plain to lavish, they are found in apartment blocks and mansions, museums, hotels, schools, administrative buildings, business premises, churches and railway stations.

Stoneware tiles: Villa Patumbah, Zurich, around 1884. Copyright: Swiss Heritage Society

Stoneware tiles: hallway at Hallerstrasse 1, Bern, around 1895. Copyright: Katja Burzer

In most cases, the historical tiles found in Switzerland or Germany are made of stoneware, the majority of which were produced by manufacturer Villeroy & Boch, which still exists in Mettlach in the Saarland to this day. The company has been using a dry-press technique patented by Englishman Richard Prosser in 1840 to produce monochrome stoneware tiles at Septfontaines in Luxembourg since 1846. The discovery of a Roman mosaic floor in Nennig, near the company headquarters in Mettlach, in 1852 inspired Eugen Boch – a highly educated hobby archaeologist – to design a floor surface that echoed the beauty of its ancient role model, but was sufficiently cost-effective to be produced in large quantities.

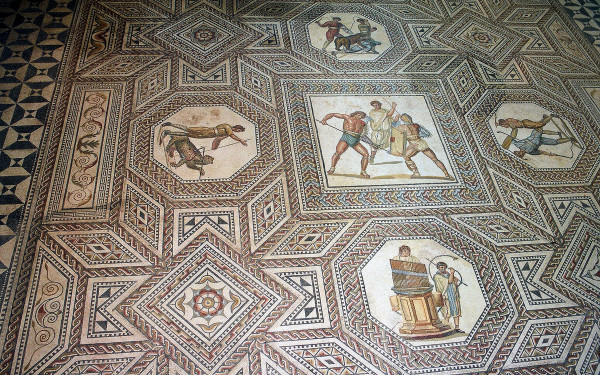

Roman mosaic floor, villa in Nennig, Saarland, 3rd century AD.

The same year, the Mettlach crockery factory began producing multi-coloured imitation mosaic tiling made of porcelain stoneware.

Stoneware tiles (Mettlach tiling), veranda at Villa Patumbah. Zurich, around 1884. Copyright: Andreas Reimann

The tiles were so successful that a separate factory was opened in 1869 especially for the production of Mettlach tiles. The name was soon on everyone’s lips – so much so that comparable products by other manufacturers were often referred to as Mettlach tiles, too. Mettlachski Plittski even entered the Russian language as an umbrella term for stoneware tiles. Boch’s “invention” left its mark on the architecture of the Gründerzeit all the way into the first few decades of the twentieth century. Stoneware tiles still grace buildings from Moscow to New York to this day. However, only tiles actually produced by the Saarland company are permitted to bear the trademark “Villeroy & Boch, Mettlach” on the reverse.

Reverse of a Mettlach tile

Villeroy & Boch rapidly blossomed into a market leader for this type of flooring. As Meyers Handlexikon des allgemeinen Wissens from 1899 states: “Mettlach produces the best cotto tiles.”

As the initial imitation mosaic surface began to go out of fashion over the years, the pattern was adapted to suit the changing tastes of the time.

Stoneware tiles: hallway, Auf der Mauer 17, Zurich, around 1900. Copyright: Katja Burzer

Stoneware tiles (Mettlach tiles), former Pius Ruff butcher’s shop, Spiegelgasse 16, Zurich, 1905. Copyright: Katja Burzer

Virtually at the same time as the invention of Mettlach tiles, the English invention of the dry stoneware press was used to produce cement tiles in the heart of the Portland cement manufacturing area in the Ardèche (France), where they were patented in 1851. While the production of stoneware tiles was limited to a format of around seventeen by seventeen centimetres, cement tiles could also be manufactured in a standard format of twenty by twenty centimetres – a fact that can still help us to quickly discern the two products.

The technique for producing cement tiles spread from France and Spain to Portugal and Italy, and from there to their respective colonies overseas, where they have survived to this day. North of the Alps, stoneware tiles dominated until around 1920. After the First World War, however, the popularity of this comparatively expensive flooring declined in Europe once and for all.

In the mid-1990s, monochrome and multi-coloured cement tiles came into fashion in Switzerland: trendy bars and shops, but also private individuals, cover floors and walls with cement tiles, and contemporary architects include the material in their designs: cements tiles are so well known today that even historical stoneware tiles are often mistaken for them. The production of the latter was also resumed in the 1990s – initially at the request of heritage preservation bodies – albeit no longer by the erstwhile market leader Villeroy & Boch. Compared to cement tiles, stoneware tiles are of higher quality, resistant to frost and de-icing salt, and easier to lay. However, they are more expensive to produce and their patterns somewhat less colourful as the pigments are burned at higher temperatures.

Einsiedeln Abbey and Engelberg Abbey are prime historical examples of the use of stoneware tiles in Switzerland.

Nave at Einsiedeln Abbey, Schwyz, floor from 1885

Detail: stoneware tiles (Mettlach tiles) in Einsiedeln Abbey. Copyright: Wilhelm Joliet

Nave at Engelberg Abbey, Obwalden, floor from 1885. Copyright: Stiftsarchiv Kloster Engelberg

Detail: stoneware tiles (Sinzig tiles) in Engelberg Abbey. Copyright: Stiftsarchiv Kloster Engelberg

In Zurich, examples of modern cement tiles can be found in the Zurich University of the Arts canteen in the Toni-Areal or the restaurant Maison Blunt in Gasometerstrasse, for instance.

Canteen at Zurich University of the Arts, Toni-Areal, Zurich, 2014, architects: EM2N. Copyright: Katja Burzer

Detail: cement tiles in the canteen at Zurich University of the Arts, Toni Areal, Zurich. Copyright: Katja Burzer

Anyone who would like to hold both types of tile in their hand can visit ETH Zurich’s Material Collection, (Hönggerberg campus), which contains historical and modern patterns by various manufacturers. Alternatively, they can visit the Material Archive’s online database to find out about the subject in more depth.

Further reading:

Desens, R.: Villeroy & Boch. Ein Vierteljahrtausend europäische Industriegeschichte 1748–1998, Saarbrücken 1998, S. 70–81, 115–121.

Euler, M.: Studien zur Baukeramik von Villeroy & Boch 1869–1914, Fliesen aus der Mosaikfabrik in Mettlach (1. Teil), Diss. Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität, Bonn 1994.

Forrer, R.: Geschichte der europäischen Fliesen-Keramik: vom Mittelalter bis zum Jahre 1900, Strassburg 1901.

Hecht, H.: Lehrbuch der Keramik. Eine Darstellung der keramischen Erzeugnisse in ihrem technischen Aufbau, Berlin/Wien 1930, S. 331–340.

Hernández Navarro, M. A.: Zementfliesen, in: Barcelona Tile Designs, Amsterdam 2006, S. 18–19.

Joliet, W.: Die Geschichte der Fliese, Köln 1996.

Lora, A. M. & Ortega, C.: El mosaico hidráulico: arte en evolución – Cement Tile: Evolution of an Art Form, Santo Domingo 2008.

Müller, W.-M.: Mit Füßen getreten – Mettlacher Platten, in: Baudenkmäler in Rheinland-Pfalz, Bd. 59, 2004, S. 103–104.

Renzi, J.: The Art of Tile, London 2009.

Arbeitskreis Keramik im HeimatMuseum Schloss Sinzig (Hrsg.): Heiß gebrannt und unverwüstlich. 140 Jahre Fliesen aus Sinzig, Meckenheim 2011.